Few authors have explored the spiritual terrain of human longing and divine truth with the grace and clarity of C.S. Lewis. In The Great Divorce, Lewis crafts an extraordinary allegorical journey that confronts the reader with the consequences of choice, the stubbornness of the soul, and the shocking simplicity of salvation. Often overshadowed by his more famous works like The Chronicles of Narnia or Mere Christianity, this relatively short but profound novel is arguably one of Lewis’s most imaginative and theologically rich endeavors.

A Visionary Premise Rooted in Spiritual Inquiry

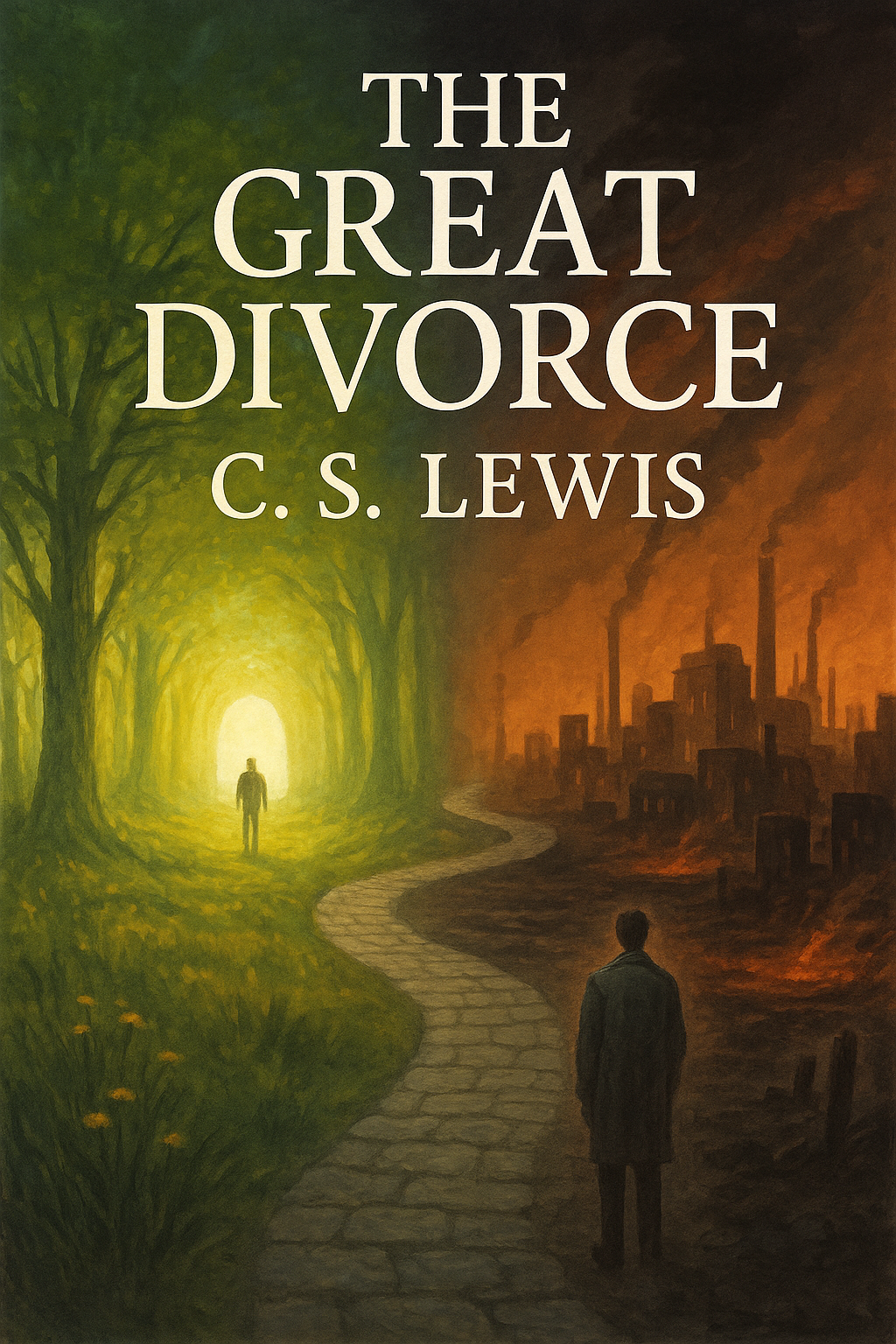

The novel begins with a deceptively simple idea: what if souls in Hell were offered a chance to visit Heaven and choose redemption? A narrator—much like Lewis himself—boards a mystical bus departing from a dreary, grey city that represents Hell, or more accurately, purgatorial self-exile. The passengers are invited to ascend to a realm of brilliant light and verdant beauty—Heaven—where they encounter shining spirits who try to convince them to stay.

But the condition is non-negotiable: they must let go of the flaws, sins, and selfish delusions that keep them tethered to their own misery.

From this premise unfolds a series of encounters, each illuminating a distinct psychological or spiritual condition that prevents people from embracing grace. Each traveler from the grey town clings to pride, vanity, self-pity, bitterness, or intellectual arrogance—emotional anchors heavier than chains.

A Tour Through the Human Soul

What Lewis achieves through these allegorical dialogues is a startlingly accurate mirror of the human condition. Each visitor’s refusal to enter Heaven reflects a familiar pathology. There’s the artist who cares more about reputation than beauty, the mother who loves possessively, the ghost of a bishop too proud of his “open-mindedness” to believe in truth.

These episodes are not dry theological debates—they are emotionally charged, piercing character sketches. They force readers to consider how the very traits we often valorize—self-sufficiency, loyalty, intellect—can become idols when they are not grounded in humility and truth.

One of the most haunting and moving scenes involves a lizard perched on a ghost’s shoulder, whispering poisonous thoughts. A shining spirit offers to kill the lizard, symbolizing lust. The ghost resists—terrified that killing it would also kill him. When he finally consents, the lizard transforms into a glorious stallion, and the ghost into a dazzling spirit. In this, Lewis illustrates not only the cost of surrendering sin but also the unimaginable transformation that can follow.

George MacDonald: Guide of Grace

In a delightful nod to literary tradition, Lewis appoints George MacDonald, a Scottish writer and Christian thinker who deeply influenced him, as the narrator’s guide. MacDonald explains the theology behind what is happening, serving as both a gentle teacher and a Socratic voice. His presence anchors the more abstract scenes with a sense of personal spiritual heritage.

The choice is meaningful. MacDonald’s theology emphasized God’s love and the ultimate possibility of salvation, themes Lewis shares but renders here with more urgency. While MacDonald leaned toward universalism, Lewis stops short of it—The Great Divorce insists that Hell is a choice, not a sentence. Anyone can leave, but few choose to.

Style and Structure: Dreamlike but Precise

Stylistically, The Great Divorce walks a fine line between dream and clarity. It is written as a dream sequence, echoing Dante’s Divine Comedy, but Lewis’s crisp prose ensures the narrative never becomes too abstract. The imagery is surreal yet grounded—beings in Heaven are so real that they are painful to touch, while the ghosts from Hell are insubstantial, barely able to bend the grass beneath their feet.

This inverted logic—where reality increases with goodness and fades with sin—is one of the book’s most profound metaphors. Hell is not a place of fire and brimstone but of increasing isolation, where people become so consumed by themselves that they vanish into nothingness.

Heaven, in contrast, is expansive, real, and full of joy—but it requires surrender, something not all are willing to give.

Theological Insight Without Preaching

What makes The Great Divorce so enduring is Lewis’s ability to discuss profound theological and philosophical concepts without alienating readers. The book is accessible even to those without deep religious backgrounds because its themes are universal: What keeps us from joy? Why do we cling to what destroys us? What does real love look like?

Lewis doesn’t claim to offer a literal description of the afterlife. In fact, he begins with a disclaimer: “The last thing I wish is to arouse curiosity about the details of the afterworld.” Rather, this is a spiritual parable meant to awaken the soul. It’s not about what Heaven and Hell look like, but what they mean.

Modern Relevance

Even today, The Great Divorce feels strikingly relevant. In an age dominated by self-actualization and personal truth, Lewis’s emphasis on surrender, humility, and moral clarity is countercultural. His characters, trapped by ego or ideology, could be taken from any modern setting. They reflect the dangers of moral relativism, the cult of identity, and the refusal to forgive.

But the book is not a condemnation—it is a hopeful call. Again and again, the spirits from Heaven plead with the ghosts to stay, to let go, to be transformed. The gates of Hell are locked from the inside, Lewis suggests. Salvation is always available. The tragedy is that most people do not want it.

A Work to Revisit

The Great Divorce is a book that reveals more with each reading. Its brevity makes it deceptively light, but its impact lingers long after the final page. It challenges the reader, not with dogma, but with vision—with the idea that our choices matter, and that Heaven or Hell may be closer than we think.

Whether you are Christian, agnostic, or simply seeking deeper understanding of the human heart, Lewis’s allegory offers a lens through which to examine life, love, and the barriers we build against joy.